Admittedly, the symbol for 28° Aries, A Large Audience Confronts The Performer Who Disappointed Its Expectations is a nightmare. And not just in the figurative sense; this is the nightmare of anyone who performs on a stage. Typically it doesn’t include being confronted by the audience, good gods. But the not being prepared part, please. Surely you’ve had some version of this dream. In a way it would almost be a relief to be confronted by the audience. Then you could sort of dialogue about it. But to disappoint an audience and have them sort of politely slink away—”the lighting was nice”—is just the worst. Or is it? My pal Justin Vivian Bond used to advise, and probably still does: “Dare to Suck.” And I gotta tell you those words have buoyed me on a number of occasions when I wasn’t quite sure if my idea of what I could do matched my ability, on stage, or in other settings requiring a leap of faith in myself. Of course it has to be a large audience, as if this wouldn’t be intimidating enough. Some performers I know would just call it an interactive workshop and own the censure as part of the experience. I’m not that clever and I’m way too sensitive. I like to be prepared. And the times that I haven’t been my best on an actual stage or a metaphoric one aren’t my favortie memories. But even they were learning experiences. My most favorite acting teacher of all time (it wasn’t Uta), Edward Morehouse used to warn against trying to wing it. It never works. There is a difference between daring to suck and winging it although, to the untrained audience eye they might be indistinguishable. If I’ve been over tired or over served and didn’t give my best performance on a stage that’s my bad because it was my responsibility to be prepared. If I was indeed prepared and stunk up the joint, well then, my side of the street is clean and I can just shrug that shite off.

Speaking of joints: I used to love to smoke marijuana. It relaxed me. I could do anything while high. Everything except act. I would never in a million years touch the stuff if I were acting in a play. And, in those couple of times I was lucky enough to be on Broadway I saw actors who would be high for rehearsals, if not performances, and it would give me panic attacks; and this was years before smoking pot myself resulted in my own actual panic attacks. Yes, there came a day, one exact moment, when it all turned on a dime and smoking weed switched from encasing me in a giant white comfy cotton ball air-conditioned parka in which I could walk to setting off bright electri red-orange lighted alarms of seizing terror. Just like that. But wait where am I going with this? I think I’m circling back. Am I? Let’s see.

Acting was a craft. It was always sacred to me. And though hardly anybody I now know has ever seen me at my craft, it really was something that I once lived and breathed. And I prided myself on being a good actor because I was always prepared. Always. I employed every fiber of my being with every amount of technique I honed, and that allowed me to fully inhabit characters in a safe, real, open, honest, accessible way. Performing was a different story. And I always made the distinction between when I was acting on a stage and when I was performing on a stage. Doing sketch comedy or improv or singing a song, even, back in the day was performing. Acting was something else. Though I don’t act really anymore—I mostly perform—when I sing now I don’t perform, I act. I wouldn’t be able to stand up and sing any other way, really, because I’m not a singer per se. I absolutely love to sing; but in order for me to sing in front of people I have to prepare the song the way I would take on a role in full-length play. Then what comes out will always be right. Even if it’s wrong it’s right. If I don’t approach a song like it’s a juicy monologue my character is compelled to communicate it falls short. Trust me, I’ve tried. I can’t put a song across on musical chops alone. I’m not an instrument that way.

However, if you know me, or if you’ve been reading this Blague, you might have come to realize that certain forces have been known to move through me. But if that’s ever happened in my work as an actor it would have taken the form of the thinnest membrane because even if I’m playing an out-of-control character, as the actor, the real me, William—not Quinn really—is in full control of what’s happening. But I have had other performance experiences where I’ve been a total instrument for those sometime friends of mine, the unseen forces.

Back in the early 1990s I worked as a waiter at the Bell Caffe on Spring Street, in New York City, while so many of my friends, now, would have been at Don Hills, literally spitting distance away. If you were around there then and remember the Bell, but didn’t realize I worked there, you are probably revising your whole concept of me. And well you should. Because on any given night as your waiter I might have been wearing a vintage micro-mini real Hawaiian print woven cotton bathing suit with oversized workboots, a hooded zip windreaker and some kind of beany as my uniform, and there would have likely been a joint hanging out of my mouth while I was taking your order. I loved waiting tables. Most waiters have nightmares that they can’t keep up with a slew of tables—see, another performance anxiety dream just when you need it—while I would dream that I had to wait on the entire restaurant by myself, which would be a very good dream indeed. Actually I could handle an entire restaurant by myself back in those days. I would love when people wouldn’t show for work. That just meant a bigger challenge to keep the entire restaurant happy and buzzing without missing a beat; and of course more cash for Billy. It is my name don’t wear it out.

So the Bell Caffe would be packed to the rafters with hipsters before there were hipsters. It was a perfect melange of punky, hip-hopping, hippy, biker, fashionista grungesters. You know, the 90s. So of course we had a live middle eastern jazz trance band on Friday nights that would come in and set themselves up in a circle right in the middle of the restaurant through which you already couldn’t walk with any semblance of ease, unless of course you were me, coursing through the place serving up a storm. Against the wall, right near where they circled up, was an old out-of-tune upright piano that looked like it was from, oh I dunno, 1910. I good quarter of the keys didn’t work at all and nobody ever played it. But one night, as the band began to play, people packed in like sardines, a thick cloud of smoke infused with garlic and pot and patchouli and incense and steamed vegetables and sweat and love and coffee and indifference hanging in the air, all my tables happy, nobody wanting for anything: I opened the piano.

I can see the keyboard now, its white keys were, wait, colored?, in my imagination—pink, blue and yellow—the black keys still black; and the music, this exotic form of jazz, was swirling and quickening into an improvisational froth, and the color-coded keys, like the sometime blueprints in my mind, urged my fingers to them in certain combinations. And I began to play. Now, as I child I took piano lessons, but it was all by rote, the Fur Elise, the Sonata in C or whatever—pieces I tried to learn and through which I only ever stumbled. But now I was in it. I was part of the band. And the piano was telling me what to play like a spool in a player piano in reverse. And I just kept forming chords and running up and down the ivories and trilling here and well, to be honest, I’m not really sure what I was doing. I was gone. Gone, daddy, gone. And the song went on forever. And I remember the hangnail I had began to bleed and I could feel the keys missing ivory scraping my fingers with raw wood edges, and on I went and it was wild and spectacular and I came as close to being possessed, and happily so, as I have ever been in my born days. And it got faster. Crescendo. Lightning speed. To beat the band. Like dancing the Alley Cat as a kid. Me and this band behind me, whom I never saw during any of this, together in a fever pitch, faster and faster and faster and then, stop, all together on a single note, done.

I was a bit out of it. Transported. My fellow waitrons were like what the fuck, why didn’t you tell us these past two years working here that you played piano? I don’t. And the band on their feet hugging me and slapping me on the back; and customers, some I knew some I didn’t, asking me when and where I would next be performing; did I have a band? did I play solo? “How can we see you?” You can’t. I don’t exist—this I.

I remember that night flashing back to another night long ago when I was a freshman in high school inappropriately attending a party of seniors where there was a band made up of bad-ass graduates who were never going to college. I was some version of drunk I’m sure; but very lucid, I recall. Still I had the pluck to join the band’s open invitation to anybody, anybody who would like to come up a sing Sweet Home Alabama. Yes that’s right. I started too high. I was in that weird strained part of my voice the whole time. However, I was working it. Showmanship up the wazoo. The full on Mick Jagger cum Bowie, with maybe some Tina thrown in, experience as applied to a Southern rock song. Sure, why not. Except that people were absolutely appalled. I would go so far as to say livid actually. When you’re fourteen giving raw androgyne glam to a room full of long-haired nineteen year olds who spent all four years of high school in auto shop, and their girlfriends for whom feathered roach clips are the de rigeur hair accessory in 1977, it’s a bit awkward to say the least. People may have thrown things. If not bottles then at least they flung the liquid contents at me. I was a shaking outcast as I left the “stage” any liquid bravado that had gotten me up there having evaporated in my spine. And then this girl grabbed me. I forget her name. But she was one of those sort of earth-shoe stoner girls, hair too thick and kinky to work a feathered roach clip. “You were great” she said, and it was clear she meant it. I began to mumble some kind of disclaimer but she interrupted me. “I know, I know”, referring to the popular opinion of my performance, banishing that pervasive thought-form with a dismissive wave of her hand and a modified Bronx cheer. “These people don’t know anything; that was great, that was truly great.”

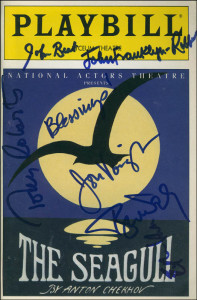

So what have we got? We have me being possessed by the spirit of some piano jazz great; and me being universally reviled but for one individual dissenting from the Large Audience Confronting The Performer. In neither case was I prepared. When I took over one of the three roles I was understudying in a Broadway production of The Seagull back in the early 90s for a few weeks, I was on stage a good amount but basically had one key line. I was universally praised for what was considered my compelling albeit silent physical life on stage; and yet Jon Voight, who was in the cast, would come to my dressing room after the show to give me a line reading or make comment on my tone, projection or modulation (on my one line!). It was so embarrassing and so infuriating. And being a sensitive young soul I thought well he must be “representing” everyone in the production and he’s been elected to come and correct me. I am ruining the entire three act play with my two dozen syllables. I wasn’t. He was just a blowhard. And apparently he is notorious for giving other actors line readings. He’s like Cloris Leachman with a overlarge dinner plate for a face and a penis that creates incestuous offspring. Gosh that felt good to say. But I am aware that I am being self indulgent in this reading of today and storytelling without much exploration of how this oracle applies to all of us. Or am I performing for a Large Audience and have I Disappointed Its Expectations. You decide.

The Bell Caffe had let me take a hiatus while I did The Seagull. And when I first went on as The Cook for the great actor and artist John Beale, Stella was attending the wedding of our closest friends, in France. The wonderful Maryann Plunkett who was in the cast made a very sweet announcement wishing me luck over the loudspeaker that piped into the dressing rooms—something I shall never forget—and after the curtain I was so keyed up with nobody to celebrate with or vent on. So I called the owner of the Bell, Krt Williams, from the backstage payphone! to see if he and other staff were still hanging out and could I come down for a drink and unwind because I was so shot through with adrenalin I could have scaled the Empire State Building. He said they were. Great. I cabbed it down to Spring Street. Meanwhile Krt had gone around to every table in the still packed restaurant telling all the customers—eek gads I’m getting teary—that I’d just gone on in this role. So when I walked into the Bell the entire room shot to their feet and applauded my entrance. I can’t tell you how amazing that felt. It was like being in an old 1930s movie. But I’m still on about me, aren’t I?

The Bell Caffe had let me take a hiatus while I did The Seagull. And when I first went on as The Cook for the great actor and artist John Beale, Stella was attending the wedding of our closest friends, in France. The wonderful Maryann Plunkett who was in the cast made a very sweet announcement wishing me luck over the loudspeaker that piped into the dressing rooms—something I shall never forget—and after the curtain I was so keyed up with nobody to celebrate with or vent on. So I called the owner of the Bell, Krt Williams, from the backstage payphone! to see if he and other staff were still hanging out and could I come down for a drink and unwind because I was so shot through with adrenalin I could have scaled the Empire State Building. He said they were. Great. I cabbed it down to Spring Street. Meanwhile Krt had gone around to every table in the still packed restaurant telling all the customers—eek gads I’m getting teary—that I’d just gone on in this role. So when I walked into the Bell the entire room shot to their feet and applauded my entrance. I can’t tell you how amazing that felt. It was like being in an old 1930s movie. But I’m still on about me, aren’t I?

The oracle, the oracle: Preparation. That’s the key element. We can’t just be hopeful. We can’t leave it to chance. We can’t expect to be possessed of a spirit. And we can’t hang our hopes on the exceptions to the rule—we have to consider the Large Audience, which symbolizes everybody, really, all of humanity. All the world is a stage. We are all players. Everybody else is the Audience. We all have a part to play and we better know that shite cold. We have Responsibility, literally: ability to respond. To what? Our purpose and our calling, so many of the themes we’ve been touching on thus far as we cycle through these Sabian Symbols. Great expectatons and Hope are not enough. So we are Confronted with the fact that we have promised more than we’ve delivered. Hope, Promise, Deliverance—these are all themes of the sign of Cancer which, in my estimation, governs this oracle. After the Fall of Gemini (duality) as befitted yesterday’s oracle on failure, we have the Flood of Cancer, the cardinal-water sign, with its’ ark (promise) to carry us to a new shore (deliverance); but it isn’t automatic, we have to prepare the vehicle for our own deliverance. Everybody, all of mankind and all life depends on our putting in that work. And, really, if it’s going to rain for forty days and forty nights you might as well stay in, put your head down, power through, and prepare! So here, as this oracle says, we haven’t done so, and we are going to be read hard by a critical mob. Good. At least the mob has the courtesy to read us instead of flinging rotten tomatoes or complimenting us on our costume with a forced smile. I think that Large Audience, as daunting as they are, are doing us a big favor. If they’re taking the time to critique us we are probably being given another chance to deliver. If they care enough to tough love us in this way then they must have seen a glimmer of hope that we do possess the right stuff to deliver. Dane Rudhyar says it comes down to “how to handle this situation.” Indeed. I think slapping on the notion of “It” being a workshop is a good one. Yes we are performing and though we mightn’t be prepared, we are preparing. And guess what, Large Scary Audience, you’re all a part of it. Maybe Jon Voight was right, maybe my tone was off, maybe he was trying to help me, maybe he’s not a face-plate after all, maybe I really learned something via his criticism, and maybe I did appreciate the fact he cared enough to come to me and try to help me. It could just as easily be that as it could be he’s a blowhard. The perception is better for me. Forget about him or any audience. What reparations are we willing to make in the process? None? Okay, then, good luck with that. But don’t expect an Audience to care enough next time to Confront you. Meanwhile it’s your responsibility to deliver; to get the job done. It’s your sacred duty to be the best most prepared You you can be. We are recovering, repairing and being delivered all the time. Every day some Audience has something critical to say; and the truth is we can always benefit from said criticism. There is always something we can learn from it. Even if the lesson in patience in enduring the criticism and still looking at that critic as a teacher, a guru. You have high expectations of others to deliver. Why shouldn’t they have high expectations of you. Maybe they think you are capable of meeting them. Isn’t even their disappointment a compliment when you think about it? Think about it. And once you have: come back more prepared and show us what you got!

Copyright 2015 Wheel Atelier Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Recent Comments